Redemption of Frank Fernandez

Frank Fernandez was 34-years-old when he began serving his prison sentence. That was back in 1993. He had been convicted of transporting drugs. It was his first serious drug offense, and his judge hammered him with a 210-month sentence. Feeling dazed when the judge slammed his hammer down on the bench, as if he’d received a knockout punch, he turned to his attorney and asked what the sentence meant. “It means 17 and a half years in prison,” the counselor told him. The news devastated Frank, as he had never been to prison before.

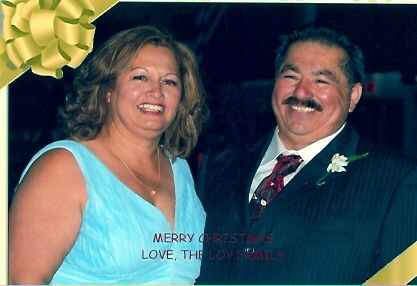

Frank and Gloria

Frank had been married to Gloria, his childhood sweetheart, at the time of his conviction. Together, they were the parents of three sons, each of whom was in his early teens. Frank had agreed to transport the drugs for local traffickers in a misguided effort to provide for his family. He had been working as a mechanic, scraping by but not thriving. The opportunity to supplement his income by carrying drugs from one city to another ended up costing him much more than his freedom.

Soon after a judge sentenced Frank to prison, Gloria divorced him. She felt that her primary responsibility was to rear the couple’s three sons. Since Frank had made the bad decisions that would separate him from the family for so many years, Gloria felt that the best way to move her family forward would be to make a clean start. Frank understood. Her decision to divorce devastated him, but he knew that he had brought the problems upon himself, with his decision to participate in drug trafficking.

Frank served the first eight years of his sentence inside the cages of secure prisons. While locked inside, he admits to having adjusted to the negative influences. Gangs were active, and to him, survival meant adhering to the ways of the penitentiary. Everyone has seen the violence and corruption of the prison on television, and Frank’s adjustment while inside fed into the stereotype. Without hope, he forgot about the world outside and made decisions that he felt were necessary to survive inside.

A consequence of Frank’s early prison adjustment meant that he served lengthy stretches in the punishment cells of solitary confinement. During the past 22 years I’ve been locked in prisons of every security level. I’ve known thousands of prisoners who, like Frank, adjusted negatively because they had lost hope. The length of sentence was so long, and the depth of loss so profound, that they could not muster the will to think about a life outside. Frank’s wife had moved on. His sons were growing from boys to men and he was incapable of playing a large enough role in their lives. After six years of confinement, his mother died. Frank felt lost to the world, as if he was living in his own tomb.

After his eighth year inside the fences, however, Frank had crossed the fulcrum. He had more time in prison behind him that he had of prison time ahead. As a consequence of more calendar pages turning, administrators adjusted Frank’s classification score and transferred him to the minimum-security camp in Taft.

The transfer to camp made all the difference in the world to Frank. Double fences that were capped with coils of razor wire no longer confined him. Since he was not caged up like a wild animal, he began to feel a bit more human. In the camp, all signs of tension were missing. Prisoners in the camp still longed for the closeness of family and community, but the absence of gang pressures along with lower tensions between the prisoners and staff lessened the perceived need to project a hard and impenetrable demeanor. Hope began its return to Frank’s life.

After a few months of good behavior in the camp, Frank qualified to participate in a community service program. He had been confined to the wrong side of prison boundaries for eight years. That long period of confinement had eroded his sense of the broader society. Once he was allowed to leave the prison camp to participate in volunteer projects that would contribute to the Taft community, Frank said that his entire adjustment changed. He began to feel as if he were living a life of meaning, as if he were something more than a prisoner.

Since 2003, Frank has slept inside the boundaries of Taft’s prison camp, but he has spent a portion of every week as a regular volunteer for community-service projects. During that time he has given more than 2000 hours, frequently working without staff supervision in the city of Taft for its residents. He performs landscaping, maintenance, irrigation, painting, light electrical work or plumbing, and general clean-up services for local nonprofit organizations. He provides needed labor for tourist attractions, recreational centers, health care providers, and churches.

The many years of contribution that Frank has given to the Taft community have changed Frank’s life. When I spoke with Frank, he was 49-years-old and only months away from his scheduled release. He had lost more than 15 years of his life to the prison system, and he struggled with the deep sense of loss that came with his separation from family. Through his community service, however, Frank felt the cleansing power that came through work. It was his act of redemption; Frank’s labor had been his way of reconciling with society for the bad decisions he had made at 34.

The responsible adjustment Frank had made with his transfer to the camp brought him a measure of respect and trust from many staff members. Like the citizens with whom he interacted in the Taft community, many staff members treated Frank with dignity, as if he were simply a fellow human being rather than a federal prisoner. Frank appreciated that courtesy, and it inspired him to prove worthy of the trust staff members extended.

The staff administrators at Taft rewarded Frank’s outstanding adjustment to camp by granting him two furloughs. During the summer of 2008, he was given permission to attend his son’s wedding. Then, in December, administrators authorized Frank to spend the Christmas holidays at home with his family. an unintended consequence of Frank’s furloughs was the rekindling of his romance with Gloria. She was giving him another chance, welcoming Frank back into her heart and into her home.

Frank had fewer than 100 days of confinement remaining when we spoke. He felt grateful for the opportunities that opened for him upon his transfer to Taft Camp. Had he remained locked inside the high-pressure atmosphere of secure prisons, Frank doubted that he would have made the positive adjustment. The negative influences would have kept him on the wrong path. With hope, however, he found a new spirit within him. After more than 15 years of imprisonment, Frank felt ready to live as a contributing citizen, doing everything he could to nurture his family.

The article on Frank brought tears to my eyes. It is a sin that Taft does not offer such opportunity to more prisoners.